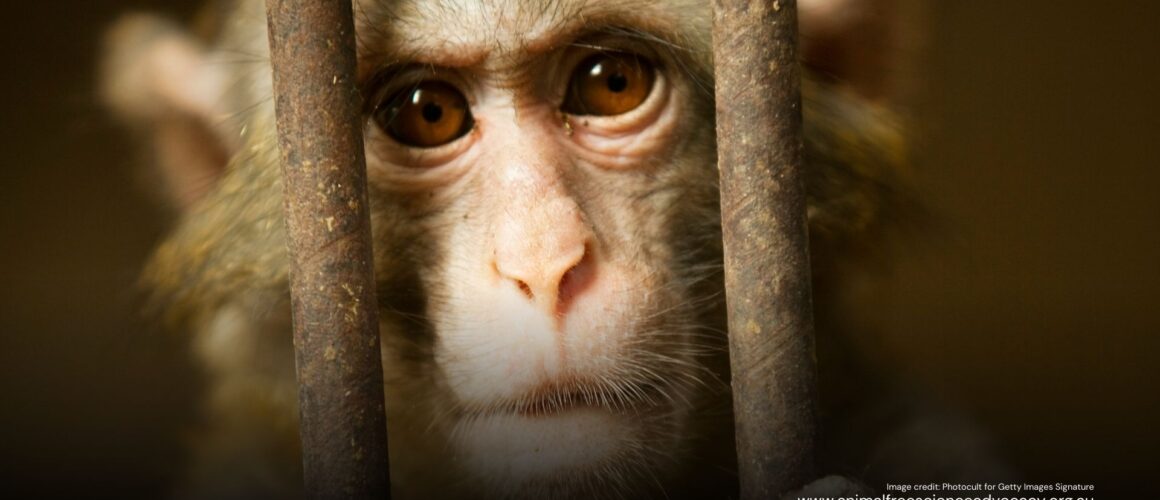

The simple image on the cover of John P. Gluck’s book Voracious Science & Vulnerable Animals (a primate scientist’s ethical journey) is that of a macaque monkey looking bewildered, her arms tucked into her lap, and an expression of uncertainty in her eyes and vulnerability in her posture.

Published in 2016, Gluck’s book is a memoir of his working life in the discipline of science, from his early university days of study to his professional life as a primate researcher and finally decades later, an animal ethicist after he vows to develop a “thinking heart”.

Published in 2016, Gluck’s book is a memoir of his working life in the discipline of science, from his early university days of study to his professional life as a primate researcher and finally decades later, an animal ethicist after he vows to develop a “thinking heart”.

Movingly, it tells of his transformation from one who uses non-human primates in scientific studies to an advocate for animals. It is a compelling book about the workings of the university research sector, the goals and aspirations of research scientists, and Gluck’s journey which he shared with humans and the non-human animals alike.

Proponents of primate research have for decades, lorded what they say are the benefits for humans by researching on monkeys. Yet, a growing voice by some (indeed researchers themselves) now questions the ethics of using monkeys in research and some have found the justifications for their use too difficult to accept. There is an increasing recognition of their sentience and an awareness of their emotional intelligence. Non-human primates such as marmosets, macaques and baboons are used in extraordinarily high numbers in medical research around the world, with many captured from the wild in their native countries and transported around the globe to wealthy countries to ultimately be used as research subjects for all manner of human ailments and conditions. In his book, Gluck describes some of the experiments in which he was involved, predominantly psychological experiments.

Gluck did not have an epiphany moment and turn from animal user to animal ethicist overnight. Instead, he describes the gradual transformation that saw his awareness surface after many years of encounters with fellow students, ethicists and with the animals themselves.

Gluck’s scientific career started with his enrolment in 1964 in biology and psychology during his graduate studies at Texas Tech University. He was then offered a position as a research assistant at the University of Wisconsin Primate Research Centre under the direction of the (in)famous Harry F. Harlow.

Harlow had become known for experiments that involved separating infant rhesus macaques from their mothers soon after birth and raising them in social isolation. Monkeys raised in isolation for the first six to 12 months of life tended to share symptoms – the isolation syndrome – consisting of fearfulness and abnormal social and sexual behaviour. Harlow created this population to determine how to cure the monkeys, with the goal of helping humans suffering from psychological disorders. These animals were known as ‘isolates’.

After internship at the Primate Research Centre Gluck took up graduate study at the University of Wisconsin in the Department of Psychology and on graduation took up a position at the University of New Mexico modernizing a primate research facility that had fallen into disrepair. It was this work that led to an involvement on ethics committees in the university and in government.

In the preface to the book Gluck tells us “The crux of the story that I tell in this book is that I slowly became conscious of the animals’ point of view and recognised that much of what I was doing as a scientist did not square with my own moral standards”.

We are drawn into the laboratory and learn of the harrowing experiments he carried out or witnessed. It does make for difficult reading at times. Then, at Chapter 4 entitled ‘Awareness’, he talks about his eventual recognition of a change in his views.

“The realiziation that something might be wrong with what I was doing with research animals came very slowly and sporadically,” he writes. “From time to time something would happen with the animals, or a colleague would raise a question or make an observation, or I would read something challenging, and the incident would cause me to reflect on the meaning and consequences of my work”.

He talks in this chapter of the long-denied self that deeply emphasised with animal suffering only to tuck it back into a dark corner of his mind. Here he acknowledges that the “hard-edged stance” adopted as an animal researcher and the knowledge that what he had invested so much time and a career on, depended on “not rocking the boat”.

He talks of fear of change and loss of identity as a respected primate researcher.

But it was a cumulative impact of events and conversations that convinced him not all was as it should be. He recalls how in 1973 one undergraduate research assistant told him he was no longer able to carry out one of his duties stating that he couldn’t “shock those monkeys anymore” in which a behavioural experiment required monkeys, raised in isolation, to receive a brief electrical foot shock to test whether the shock elicited bouts of self-injuries behaviour. Although another student stepped in to undertake the studies the assistant’s ethical dilemma did not leave the mind of Gluck.

He also recounts a jolt to his complacency about animal research when a veterinarian at the Facility at the University of New Mexico with involvement at the chimpanzee colony at the Holloman Air Force Base in Alamogordo where the chimps were housed in dark maximum-security-prison type housing and where both the vet and Gluck were appalled at the conditions. The vet expressed his sentiment that the chimps were paying an inordinate price for the space research. Together the two men felt they could comfortably discuss animal issues openly with each other from then on.

He tells of other instances that raised awareness along the way including that of a young woman who, in around 1976, was enrolled in his animal behaviour class and who offered Gluck a loan of Peter Singer’s seminal book Animal Liberation. Another source of questioning came from his involvement in the University’s Animal Care Committee.

But it was the monkeys themselves, the individuals whom he had become to know, who made it increasingly difficult to maintain the emotional distance required by the rules of scientific objectivity. Previously desensitized to their complex inner lives, and the self-conscious awareness of their circumstances, it became apparent to him that he had in the past, chosen for various reasons to ignore it.

But it was the monkeys themselves, the individuals whom he had become to know, who made it increasingly difficult to maintain the emotional distance required by the rules of scientific objectivity. Previously desensitized to their complex inner lives, and the self-conscious awareness of their circumstances, it became apparent to him that he had in the past, chosen for various reasons to ignore it.

After decades involved in animal research it was in the 1990s that Gluck moved away from it altogether and devoted himself to the complexities of animal research ethics and clinical psychology. He is now Professor Emeritus at the Department of Psychology, University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, USA.

Gradually as the memoir progresses, the reader witnesses the reckoning taking place for Gluck.

There is a good deal of bravery in someone who can publicly talk about the horrors they have witnessed. Recounting one’s uncomfortable past is not always an easy task but as a reader of this book, I was most grateful for the author’s honesty and compassion.

This beautifully written book underlies the message of the power and truth of allowing our actions to align with our heart, no matter the length of time it takes to recognise and reconcile.

It is a book of reflection; a memoir that I strongly invite you to read for an insight into what is usually hidden from us. It is a beautifully written journey of awareness.

To be honest, it is a book I would like each primate researcher in this country to read.

Review by Robyn Kirby, Research Officer, HRA

To find out more about primate experiments in Australia please visit our Ban Primate Experiments page here