A brief history of the movement from the 1800s

This page is dedicated to those activists upon whose shoulders we stand. It provides a brief history of the anti-vivisection movement from the 1800s, the prominent campaigns and campaigners. We hope this is a useful resource for those interested in the history of the movement.

There is a common misconception that the anti-vivisection movement is a modern one. However, it originated in 19th Century England when vivisection was highly debated. The anti-vivisection movement in the period 1860 to 1910 was one of the strongest debates of the time. The early anti-vivisection movement was led by women, many of whom were also prominent feminists and women’s right activists. Here we feature some of the activists.

Anna Kingsford

(1846 – 1888)

Anna Kingsford was an English feminist, vegetarian and anti-vivisection activist.

In order to support her anti-vivisection activism Anna Kingsford studied medicine. After passing her first examination in London in 1872 she continued her education in Paris. During classes she protested when vivisection would take place. Often the only woman in her class, she endured further persecution for her animal rights activism yet she continued to take a stand. At the age of 33 in 1880, she graduated and was the first English woman to receive a degree in medicine. However, as a woman she was not permitted to practice as a doctor. She devoted the rest of her life to writing and speaking on behalf of animals.

She died at the age of 41 in 1888. It was 4 years after her death in 1892 the British Medical Association finally accepted female doctors. A remarkable woman ahead of her time.

Frances Power Cobbe

(1822 – 1904)

Frances Power Cobb was an Irish writer, social reformer and leader in the women’s’ rights and anti- vivisection movements. She was a leading suffragette.

In 1875, she founded the world’s first organization dedicated to campaigning against vivisection, the National Anti-Vivisection Society and in 1898 the British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection (which today continues its work and is now known as Cruelty Free International.

Frances Power Cobbe was instrumental in drafting the Cruelty to Animals Act 1876.

In 1884 she retired to Wales and at the age of 82 she died of heart failure at her home in 1904.

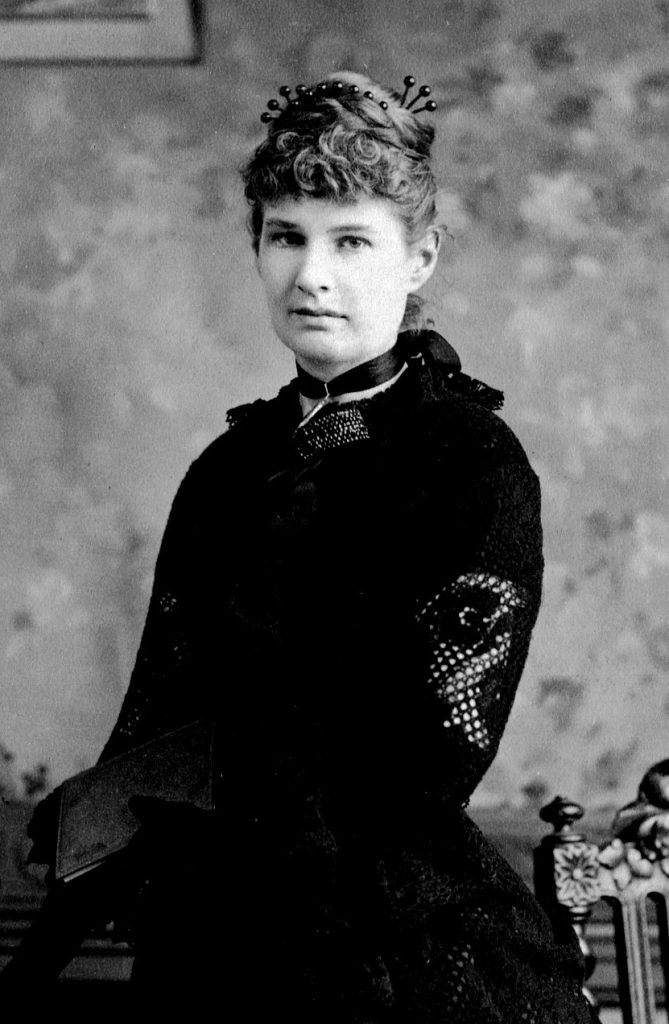

Louise (Lizzy) Lind af Hageby

(1878 – 1963) (pictured) and

Leisa Katherine Schartau

(1876 – 1962) (no image recorded)

Lind af Hageby and Schartau were two Swedish feminists and animal rights activists who founded the Anti-vivisection Society of Sweden. Lind af Hageby also lectured on the white slave trade, prison reform, and social reform.

In 1902, in order to gain medical training to support their campaigning, both women enrolled at the London School of Medicine for Women, a vivisection-free college that had visiting arrangements with other colleges. Here they infiltrated the male-dominated medical fraternity. They attended hundreds of lectures and demonstrations at King’s and University College, including experiments on live animals. In 1903 the women attended a lecture conducted by Ernest Starling and William Bayliss where they witnessed the vivisection of an un-anesthetised dog in front of some 60 medical students. This same dog was used in multiple procedures over the course of a few months and soon after the dog was killed.

This dog was first used in vivisection in December 1902 by Starling, who cut open the dog’s abdomen and ligated the pancreatic duct. For the next two months, the dog lived in a cage until Starling and Bayliss used him again for two procedures on 2 February 1903, the day Lind and Schartau were present. The women alleged that Bayliss illegally dissected the dog while it was awake.

Stephen Coleridge, a lawyer opposed to animal experiments, was horrified by the account and made a public accusation that Bayliss had broken the law and tortured the dog. However, Bayliss sued Coleridge for defamation and a jury found Coleridge guilty of defamation and ordered him pay Bayliss damages and legal fees.

Animal rights campaigners were outraged at the trial’s result and raised money to have a bronze statue of the dog erected in Battersea, London, in 1906.

Below the statue was an inscription:

“In memory of the brown terrier dog done to death in the laboratories of University College in February 1903 after having endured vivisection extending over more than two months and having been handed over from one vivisector to another till death came to his release. Men and women of England, how long shall these things be?”

Medical students were angered by its provocative words leading to frequent vandalism of the statute and requiring 24-hour police guard. On 10 December 1907 fury was transformed into action with 1,000 medical students marching through central London waving effigies of the brown dog, clashing with suffragettes, trade unionists, and 400 police officers in one of a series of battles known as the Brown Dog riots.

Sporadic violence continued after this, with students disrupting meetings organized by Lizzy Lind af Hageby. Trade Unionists, socialists, and women’s activists fought battles with students in the vicinity of the Brown Dog Memorial to prevent its destruction.

However, in March 1910, Battersea Council sent 4 workers accompanied by 120 police officers to remove the statue under cover of darkness. It was reportedly melted down by the council’s blacksmith, despite a 20,000-strong petition in its favour.

There was significant opposition to vivisection in England in both houses of Parliament during the reign of Queen Victoria (1837–1901). The Queen herself was strongly opposed to it as were writers George Bernard Shaw and Mark Twain.

Vivisected Jack

Another hapless dog to make history in the anti-vivisection movement was an Irish Terrier who became known as Vivisected Jack. In 1913, after disappearing for six weeks, Jack returned walking on 3 legs with a collar bearing the words “Surgical Department”.

The story can be found here

In Melbourne in 1922, a branch of the British Union Against Vivisection (BUAV) was established with Miss Helena MacDougall being appointed as the first Secretary.

In the 1930s other branches of the BUAV were established around Australia notably in Western Australia and Tasmania where the President in 1935, The Hon E Dwyer-Gray, was also Treasurer of the State of Tasmania and who went on to become Premier from June – December 1939.

Indeed, it was not unusual, during the 1930s, for government ministers to be anti-vivisectionists.

It has been noted that every British Cabinet at that time had included a strong minority of uncompromising anti-vivisectionists.

In 1979 the Australian Association for Humane Research (AAHR) was established by Ms Elizabeth Ahlston in Sydney. It was registered under the Charitable Collections Act (NSW) on 13th December 1979 and incorporated on 6th January 1992. In March 2005, AAHR underwent considerable change. After over 25 years of undoubted commitment and dedication to the cause, Ms Ahlston decided it was time to move on and HRA was handed over to a new Management Committee and relocated to Melbourne.

From this point, HRA was led by Helen Marston, who retired in 2020 and sadly passed away in 2021. HRA became Animal-Free Science Advocacy in October 2024.

More information about HRA’s history can be found here.

Further Resources of Interest

A collection of historical animal rights publications, including anti-vivisection, can be found at the State Library of Victoria

This resource includes a number of Australian publications as does the National Library of Australia

The Oxford Centre for Animal Ethics offers a very interesting video ‘Oxford: The Home of Controversy about Animals’ covering some of the University of Oxford’s very prominent academics in history who opposed vivisection. Those referred to include CS Lewis, John Wesley, and writer, Lewis Carroll. The video is presented by the Rev Prof Andrew Linzey who, himself, gave the first lectures on the theology of animal rights at the University decades ago.

The NC State University Libraries (USA) Animal Rights and Welfare collection documenting the social, cultural, legislative, political and intellectual history of animal welfare and animal rights can be found here.

Animal-Free Science Advocacy holds a number of historical documents and ephemera including campaign brochures from Australia and internationally.

An interesting account of the history of the growth of the animal experimentation industry can be read in the book Rat Trap by Dr Pandora Pound.

Podcast and article about the Brown Dog by Animal Turn here.

References and credits:

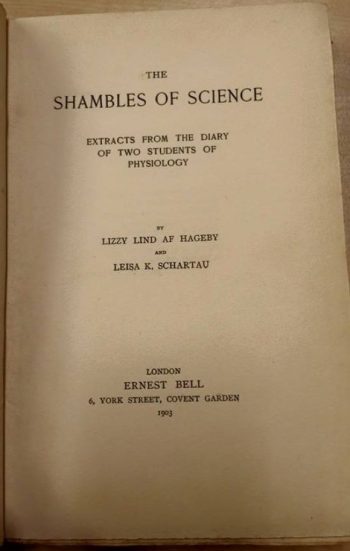

The Shambles of Science: Extracts from the Diary of Two Students of Physiology (1903). Lizzy Lind-af-Hageby and Leisa K. Schartau – London, Ernest Bell – “First edition, July 1903”. Courtesy of and used with permission from Ernest Bell Library Collection.

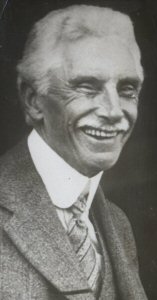

Image: Hon E Dwyer-Gray – National Library Australia (Archives of Tasmania)