There are environmental consequences of both animal and non-animal based research. However, animal based research generates additional environmental costs, which is often an overlooked issue when considering the harms of animal research.

An analysis of the environmental impacts of animal use in experimentation and education in Australia is essentially non-existent. Initially, greater transparency in the complete number of animals used during the entire experimentation and education process, including those bred as part of genetic modification even if they are not ultimately used in experimentation, would expose the environmental inefficiencies of the current methods of research and highlight the areas for improvement and change.

Breeding and genetic modification

There are a number of facilities across Australia where animals are bred specifically for experimentation. These facilities include industry owned (1), government supported (2), and university departments (3).

The National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) code (4) considers genetic modification in animal breeding as a scientific purpose (2.4.26) and subject to Animal Ethics Committee (AEC) approval to prevent over-breeding. This means some of the animals bred for the purpose of research may be genetically modified.

Some non-genetically modified animals such as mice may be sent to sanctuaries for use as a food source in species conservation (5). However, animals who have been genetically modified are required to be “decontaminated by autoclaving, incineration or any other method approved in writing.”(6). Animals who are not genetically modified but who have been exposed to genetically modified micro-organisms, “must be treated as if [the animal] were GM.”

Environmental concerns are raised in the possibility of an accidental release or escape of genetically modified species and interbreeding with wild or native populations (7).

Resource Consumption

Australia emits three times the global average of carbon dioxide emissions per capita each year (8) and uses approximately one animal in research and teaching for every three people (9). This is compared to one animal for every fourteen people in the United States, and one for every twenty in the United Kingdom.

Many countries with similar government and university infrastructure as Australia have committed to reducing their emissions by up to 45% by 2020. However, the Australian government’s commitment was 5% by 2020 to which it achieved just 1.6% (10). These figures and results may significantly impact the energy strategies and efficiency applications of government owned and operated research facilities and private facilities which are often influenced by the standards of the government.

Under the NHMRC code, “measures should be taken to ensure that the animal’s environment and management are appropriate for the species and the individual animal”. To ensure the comfort and required maintenance of animal environments, research laboratories require significant amounts of energy, up to ten times more per square metre than common office buildings (11). This includes powering ventilation fans, heating, cooling, storage, and transport, in addition to water usage.

Outside of the government’s emissions reduction targets, non-government facilities have developed their own plans attempting to reduce their environmental impact (12).

Depending on the level of biosecurity at a facility, there may be further energy and infrastructure requirements (13) to maintain a strict enclosed laboratory, including power supply and exhaust systems (14), in addition to increased air handling units, advanced cleaning procedures, and containment amenities (15). Bio secure laboratories may also have the requirement of being a building independent of others in the facility with independent power and airflow systems.

Waste

Housing animals requires significant resources and care to be dedicated to their survival, despite the procedures which they may be subjected to. Waste from animal presence and housing includes excrement, bedding, and excess food, in addition to the requirements of the experimentation such as syringes, needles, and gavages (16).

The animals’ bodies are considered as waste for disposal purposes and can be associated with hazardous exposure depending on the studies performed on them. Services transporting the animals and waste outside of the laboratory may be “unaware of what they are handling and the corresponding hazards it may pose”, (17) and may not be as cautious of risks associated with the material as the laboratory may be.

Industries using animals for toxicity and pharmaceutical testing may be contributing to groundwater and soil contamination due to runoff from improperly managed laboratory waste handling, removal, and disposal.

Chemicals

The safety (toxicity) and efficacy testing of chemical compounds is one of the key reasons why animals are used in experiments. Even when the research is not related to toxicity testing, they are still used for sanitation, disinfection, and sterilisation (16). Some chemicals used for experimentation may have unknown hazardous or carcinogenic properties.

Highly toxic chemicals are also often used to preserve specimens for educational dissections and for veterinary training. Exposure to these substances without appropriate protective equipment can create significant health and environmental hazards. Veterinary schools with high safety standards have failed to meet compliance and may suggest a wider problem with safety surrounding toxic chemicals (18) and improper use and handling of chemicals during procedures or training can expose toxins to the environment beyond the controlled facility.

Some dissection suppliers have acknowledged the risk of preservation chemicals and supply their specimens frozen. (19)

Pollution

Diseases caused by pollution are responsible for 16% of deaths worldwide (20) and there is possible interaction between air pollutants and gene expression affecting human health (21).

Waste from laboratories disposed of by incineration may contain 10-25% of substances which are “hazardous to humans or animals and deleterious to the environment” (22). Particulate matter, organic compounds, pathogens, and radioactive materials may be released as part of the incineration process and exposed into the surrounding environment.

Exposure to these substances poses risks to human health including cancers and respiratory illnesses. Environmental and planetary health risks include: air and water pollution, acidification, and greenhouse gas emissions in the surrounding environment.

The effectiveness of the incinerator in removing these human health and environmental health risks is reliant upon the facility’s management and the facility itself. Accidental spills and mishandling “may release as much or more toxic materials to the environment than the direct emissions. (23)

Development of Attitudes

Ethical and ecological appreciation of animals occurs during children’s time through eighth to eleventh year levels at school, approximately 13 to 16 years of age (24). This is often also the time when classroom animal dissection is introduced into science lesson plans.

The presence of animal dissection in science classes and discussion of animals as ‘tools’ or ‘learning instruments’ during a vulnerable and key ethical development stage of life, alongside influenced dietary and lifestyle experiences, may contribute to the degradation of the appreciation of animals and the formulation of categories of animals with which people interact during their adult years, and the subsequent impact of these attitudes on the environment.

Animal-Free Research Methods

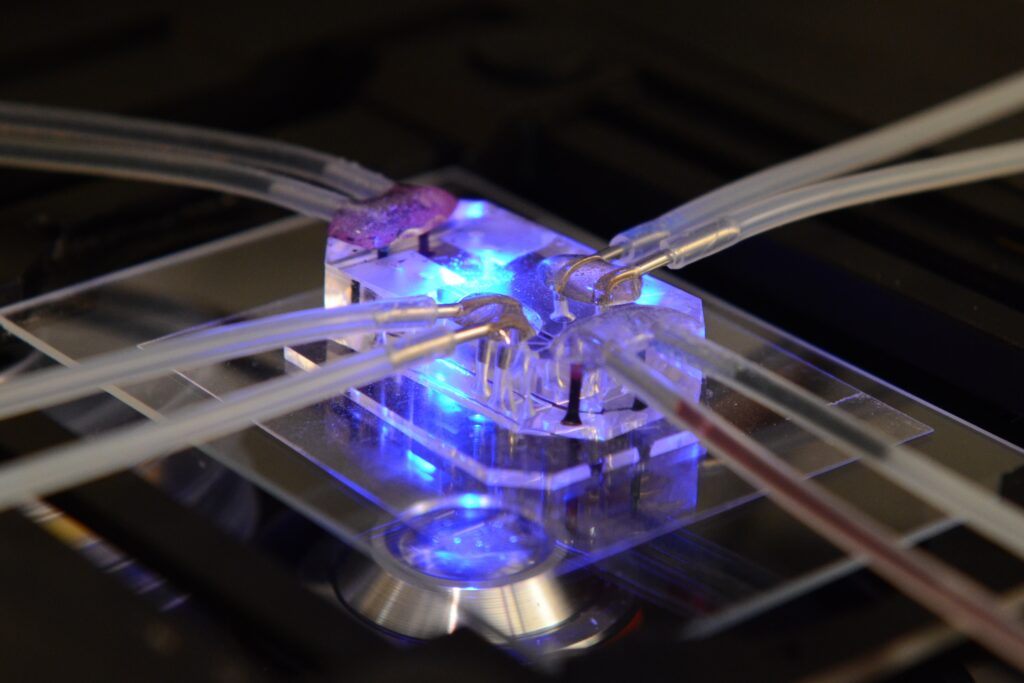

Many animal-free methods of research use sophisticated computer software which requires climate-controlled environments, data processing facilities, and bio secure storage for tissue samples and cell cultures. However, the considerable reduction, elimination, or multiple-use applications of samples without waste (eg. toxicology testing using a lung-on-a-chip instead of an LD50 test on a mouse), along with a reduction or elimination of transportation, breeding, housing, and physical observation will significantly reduce the energy requirements for research laboratories.

Animals can impact the environment in ways which a computer simulation or tissue sample cannot. Non-animal methods of research cannot escape and spread disease or breed, they do not have lives or deaths which require maintenance or disposal, and they can be endlessly modified without the ethical and ecological impacts of genetic breeding or wild capture.

As many of these ‘alternatives’ to animal use require equipment, either for manufacturing or the laboratory tools themselves, transported from overseas, there may be requirement for these to be transported by air freight. Researchers may also participate in training for use of new methods of research at international locations.

Small-scale medical waste from methods such as bio samples will still require bio-secure disposal at a small environmental cost, and the storage of ethically sourced cadavers may require the use of preservation chemicals.

Using digital, virtual, or synthetic models of dissection while adding education about the ecological impact of human interaction with animals during a crucial developmental stage of young adults may reduce the levels of speciesism amongst those transitioning from school- to working-age and encourage cognitive consideration of the impact of individual choices on animals and the environment.

Global Animal Protection

In 2015, the United Nations (UN) adopted 17 goals as part of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (25). In the absence of any formal or direct agenda for animal protection, a number of the sustainable development goals (SDG) (26) may be used as encouragement to return positive impacts for animals, those being ‘Good Health and Wellbeing’, ‘Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure’, and ‘Responsible Consumption and Production’ (27).

Visualisations of the goals (28) reveals that Australia has an opportunity to further develop the value of medium and high-tech industries by increasing domestic manufacturing and implementation of alternatives to animal use in research, and to increase human-relevant health by developing appropriate solutions to human issues. With animal research driving human-health initiatives there is an opportunity to improve human health, animal health, and environmental health simultaneously through the development, manufacture, and adoption of animal-free alternatives.

However, the UNSDGs fall short in that they consider only domestic material consumption and fossil-fuel subsidies as ‘Responsible Consumption and Production’ measures. Reliance on consumption of animal-derived medicines cannot be sustained ethically or environmentally and the production of responsible alternatives can increase the key measures of good health and wellbeing.

In the absence of measures promoting sustainable human health development, the UN Convention on Animal Health and Protection (UNCAHP) (29) has been developed to protect animals at the global level by universally adopting the 3Rs, recognising the fundamental interests of animals, and development and promotion of alternatives to existing animal products and exploitation.

The pursuit of human knowledge and scientific advancement will always come with an environmental impact. However, that impact can be significantly reduced by embracing energy efficient and ethically sustainable research methods and processes.

In Victoria, AFSA has joined CDS Victoria, allowing our supporters to contribute to our fundraising goals through bottle and can recycling. Simply choose Animal-Free Science Advocacy as the charity for which your refund will be deposited when delivering your recycled containers at designated outlets. All refund points have options to donate to community groups and organisations on the spot. For registered Visy community members, choose Animal-Free Science Advocacy as the selected charity when selecting your payment method, or use the below barcode or Zone ID.

Zone ID C2000010166

Support Our Work

Help us to advocate for an end to animal experimentation and to reduce the environmental impact of this industry by phasing out animal testing.

Learn More

Animal-free research methodologies offer more accurate, safe, human-relevant and reliable ways to conduct research compared to using animals.

References

1 www.abr.org.au/

2 www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Environment_and_Communications/EPBC_Live_Primates_Bill/Report/c01

3 researchdata.edu.au/national-non-human-research-facility/96736

4 https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/publications/australian-code-care-and-use-animals-scientific-purposes#block-views-block-file-attachments-content-block-1

5 www.abr.org.au/about/environmental-impact

6 www.adelaide.edu.au/staff/research/system/files/media/documents/2019-10/gmo-facility-guidelines-pc1.pdf

7 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25032294/

8 ourworldindata.org/grapher/co-emissions-per-capita

9 Population of Australia (26,595,991 at February 2024) divided by the average approximate conservative number of animals used in Australia over five years 2013-2017 (10,075,222) equals 2.63

10 reneweconomy.com.au/australia-will-not-hit-its-2020-emissions-reduction-target-till-2030/

11 Cubitt, Steven & Sharp, G.. (2011). Maintaining quality and reducing energy in research animal facilities. Animal Technology and Welfare. 10. 91-97+117+122+127.

12 www.tecniplast.it/au/company-profile.html

13 www.advancetecllc.com/classifications/bsl-bio-safety-level

14 consteril.com/biosafety-levels-difference/

15 www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/biocontainment

16 www.mdpi.com/2076-3298/1/1/14

17 www.medlabmag.com/article/1111/

18 www.altex.org/index.php/altex/article/view/766/784

19 dissectionconnection.com.au/faqs/

20 www.thelancet.com/commissions/pollution-and-health

21 www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0160412019335512

22 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23612530/

23 Human Health Risk Assessment Protocol, United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2005

24 www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1001&context=acwp_sata

25 sdgs.un.org/2030agenda32 sdgs.un.org/goals

26 x-cellr8.com/2023/03/31/united-nations-sustainability-development/

27 unstats.un.org/sdgs/dataportal/countryprofiles/AUS#goal-9

28 www.uncahp.org